Clojure Scripting

Clojure is a dialect of the Lisp programming language. Clojure is a general-purpose programming language with an emphasis on functional programming.

Contents

- 1 Clojure tutorial for ImageJ

- 1.1 Using Clojure inside Fiji

- 1.2 Language basics

- 1.3 Calling methods and variables on a java object

- 1.4 Calling static fields and methods: namespace syntax

- 1.5 Defining variables: obtaining the current image

- 1.6 Creating objects: invoking constructors

- 1.7 Defining a closure

- 1.8 Manipulating images

- 1.8.1 ImageJ Image internals: ImagePlus, ImageProcessor, ImageStack

- 1.8.2 Conventions in naming image variables

- 1.8.3 Creating a new image

- 1.8.4 Creating an image of the same type of an existing one

- 1.8.5 Resizing an image

- 1.8.6 Resizing an ImageStack

- 1.8.7 Resizing an image or ImageStack using ROIs

- 1.9 Manipulate images using ImgLib

- 1.10 Looping an array of pixels

- 1.11 Executing commands from the menus

- 1.12 Creating and using Clojure scripts as ImageJ plugins

- 1.13 Using java beans for quick and convenient access to an object's fields

- 2 Examples

- 3 Appendix

- 3.1 Defining the output stream

- 3.2 Destructuring

- 3.3 Namespaces

- 3.4 Forget/Remove all variables from a namespace

- 3.5 JVM arguments

- 3.6 Reflection

- 3.7 Lambda functions

- 3.8 Built-in documentation

- 3.9 A fibonacci sequence: lazy and infinite sequences

- 3.10 Creating shallow and deep sequences from java arrays

- 3.11 Generating java classes in .class files from clojure code

- 3.12 References, concurrency, transactions and synchronization

- 3.13 Using try/catch/finally and throwing Exceptions

- 3.14 Executing a command in a shell and capturing its output

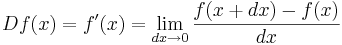

- 3.15 Creating a derivative of a function

- 3.16 Pretty printing a primitive array

- 3.17 Loading an image file into a byte array

Clojure tutorial for ImageJ

Check out clojure web site and particularly the chapter on Java interoperability.

Clojure is not a scripting language: Clojure compiles directly to JVM bytecode, and thus runs at native speed. Thus one must think of Clojure as a true alternative to Java the language, but much more expressive, flexible and powerful.

See also:

- Clojure Cookbook.

- The Clojure API (listing of all available functions, with explanations).

- Clojure cheat sheet: a summary of all the essentials.

Using Clojure inside Fiji

Go to Plugins › Scripting › Clojure Interpreter. The prompt accepts any clojure code. See also Fiji's Script Editor.

See Scripting Help for details on keybindings and how to use the interpreter. ^ Ctrl+) will add all necessary ending parenthesis.

A minimal, complete clojure example:

(import '(ij IJ)) (def gold (IJ/openImage "https://imagej.net/images/AuPbSn40.jpg")) (.show gold)

To create scripts, just save them as .clj text files (with an underscore in the name) in any folder or subfolder of Fiji's plugins folder, and run Plugins › Scripting › Refresh Clojure Scripts to update the menus (it's done automatically at start up as well).

To edit a script, just edit and save it with your favorite text editor.

To execute a script, do any of:

- Select it from the plugins menus.

- Type 'l' (L), start typing its name, push the down arrow and then return to execute it.

- If it was the last executed command, just type ⇧ Shift+R (shortcut to "Process - Repeat Command").

The script is always read directly from the source file, so no updating of menus is needed (unless its file name changes).

Convenient Clojure in Fiji with Funimage

- Funimage provides a library for convenient Clojure coding within Fiji. Alleviating much of the need for type-hinting, and some of the burdens involved in handling more complicated data structures, such as those from ImgLib2.

See the list of update sites for information on setting up the Funimage update site.

Running Clojure files from the command line

Fiji can execute any clojure file directly:

./fiji plugins/Examples/blend_two_images.clj

The file will run with the full classpath as set by fiji, which includes all jars in fiji/jars and fiji/plugins/ folders, among others.

Getting a REPL without the usual ImageJ GUI

The simplest is:

./fiji --clojure

... which you may enrich with memory settings, incremental garbage collection (works great for multicore CPUs), the enhanced JIT (server flag), and a debugger agent (and any other JVM flag):

./fiji -Xmx2000m -Xincgc -server -agentlib:jdwp=transport=dt_socket,address=8010,server=y,suspend=n --clojure --

Above, notice the ending double dash -- which separates Fiji/JVM options from ImageJ options (in this case, none).

For a nicer Repl, you may want to run the clojure.lang.Repl via the jline.ConsoleRunner, which gives you up and down arrow navigation, etc:

./fiji -Xmx2000m -Xincgc -server -agentlib:jdwp=transport=dt_socket,address=8010,server=y,suspend=n \

--main-class jline.ConsoleRunner -- clojure.lang.Repl

Note that we put the double-dash between jline.ConsoleRunner (the main class to launch) and clojure.lang.Repl (its arguments).

If no JVM arguments were specified, there's no need for the double dash:

./fiji --main-class jline.ConsoleRunner clojure.lang.Repl

Just make sure to have the jline.jar in your classpath (or drop it into fiji/jars folder).

Debugging with the Java Debugger

If you have launched fiji with an agentlib, you may then connect to it via the jdb:

First launch fiji with the agentlib:

./fiji -agentlib:jdwp=transport=dt_socket,address=8010,server=y,suspend=n --

Then connect, at the same port address:

cd fiji/java/linux/jdk1.6.0_12/bin/ ./jdb -attach 8010

Which gives you a jdb prompt after printing:

Set uncaught java.lang.Throwable Set deferred uncaught java.lang.Throwable Initializing jdb ... >

Now you may query about threads:

> threads Group system: (java.lang.ref.Reference$ReferenceHandler)0x72b Reference Handler cond. waiting (java.lang.ref.Finalizer$FinalizerThread)0x72c Finalizer cond. waiting (java.lang.Thread)0x72d Signal Dispatcher running

And suspend all to see the stack trace of each thread:

> suspend > where 0x72d [1] java.io.FileInputStream.read (native method) [2] jline.Terminal.readCharacter (Terminal.java:99) [3] jline.UnixTerminal.readVirtualKey (UnixTerminal.java:128) [4] jline.ConsoleReader.readVirtualKey (ConsoleReader.java:1,450) [5] jline.ConsoleReader.readBinding (ConsoleReader.java:651) [6] jline.ConsoleReader.readLine (ConsoleReader.java:492) [7] jline.ConsoleReader.readLine (ConsoleReader.java:446) [8] jline.ConsoleReader.readLine (ConsoleReader.java:298) [9] jline.ConsoleReaderInputStream$ConsoleLineInputStream.read (ConsoleReaderInputStream.java:92) ...

There are perhaps more convenient setups built into Eclipse, IntelliJ, NetBeans and other IDEs that support Clojure via plugins, but the jdb gives you what you want very quickly.

Within the jdb prompt, type "help".

Language basics

- A ';' defines the start of a comment, just like '//' does in Java.

- A function definition declares parameters within [].

- Local variables are declared with let, and global variables with def.

- Functions are defined with defn, and are visible globally. Hence a function declared within a let statement has access to variables declared in it. This method enables closures.

Importing classes

To reference Java classes from Clojure you will need to import them.

You can specify imports in Clojure in a few ways:

; A single import.

(import java.util.Date)

; Use it!

(def *now* (Date.))

(str *now*)

; Multiple imports at once.

(import '(java.util Date Calendar)

'(java.net URI ServerSocket)

java.sql.DriverManager)

; Import multiple classes in a namespace.

(ns foo.bar

(:import (java.util Date

Calendar)

(java.util.logging Logger

Level)))

Calling methods and variables on a java object

There are two ways, the second syntactic sugar of the first. Below, imp is a pointer to an ImagePlus:

; java-ish way: (. imp (getProcessor)) ; shorter java-ish way: (. imp getProcessor) ; lisp-ish way: (.getProcessor imp)

To call a method on an object returned by a method call, there is a simplified way:

; double way: (. (. imp (getProcessor)) (getPixels)) ; simplified double way: (.. imp (getProcessor) (getPixels)) ; super simplified (less parenthesis than java!) (.. imp getProcessor getPixels) ; or lisp-ish way: (.getPixels (.getProcessor imp))

Any number of concatenated method calls, both for static methods or for instances:

; Concatenated call to static and instance methods (.. WindowManager getCurrentImage getProcessor getPixels)

To call a variable or 'field', just do it like a method call but without the parentheses:

(. imp changes)

or more lisp-ish:

(.changes imp)

To enhance readability, use import when appropriate. Imports remain visible throughout the current namespace:

(import '(java.awt Color Rectangle)

'(ij.plugin.filter PlugInFilter))

(new Rectangle 0 0 500 500)

; It's the same as:

(Rectangle. 0 0 500 500)

; A static field, call like a namespace:

PlugInFilter/DOES_ALL

Choose whatever matches your mental schemes best.

Calling static fields and methods: namespace syntax

To call a static field or method, use namespace syntax:

(println "does all: " ij.plugin.filter.PlugInFilter/DOES_ALL) (ij.IJ/log "Some logged text")

Above, notice how a class name is used instead of a pointer to call static fields and methods. Static fields and methods are just variables and functions that exist within the namespace of the class in which they are declared. Hence Clojure's namespace syntax makes way more sense than java code, that doesn't do such distinction and allows for loads of confusion (java allows invoking static methods and fields using a pointer to an instance of the class in which such static methods and fields are declared).

Defining variables: obtaining the current image

As a local variable imp declared within a let statement:

(let [imp (ij.WindowManager/getCurrentImage)]

; print its name

(println (.getTitle imp)))

; Variable imp NOT visible from outside let statement:

(println (.getTitle imp))

---> ERROR

As a general variable visible from the entire namespace:

(def *imp* (ij.WindowManager/getCurrentImage)) (println (.getTitle *imp*))

By convention, in lisp global variables are written with asterisks in the name.

A let statement lets you declare any number of paired variable name / values, even referring to each other in sequence:

(let [imp (ij.WindowManager/getCurrentImage)

ip (.getProcessor imp)

pix (.getPixels ip)

pix2 (.getPixels (.getProcessor imp))]

; do some processing ...

(println (str "number of pixels: " (count pix))))

Any number of let statements may be nested together:

(let [imp (ij.WindowManager/getCurrentImage)]

; do whatever processing here

(let [ip (.getProcessor imp]

; print first pixel

(println (str (.getPixel ip 0 0))))))

Creating objects: invoking constructors

A constructor is invoked by adding a dot '.' to the name of a class, followed by the arguments. Below, we create an ImageProcessor and then an ImagePlus with it, and finally we print the ImagePlus, which invokes toString() on it (like in java):

(let [ip (ij.process.ByteProcessor. 400 400)

imp (ij.ImagePlus. "my image" ip)]

(println imp))

An alternative syntax is to use the java-like new keyword, but it's unnecessarily verbose:

(let [ip (new ij.process.ByteProcessor 400 400)

imp (new ij.ImagePlus "my image" ip)]

(println imp))

Defining a closure

In the following a function is declared within the scope of the local variable rand, which contains an instance of java.util.Random. All calls to the function rand-double will use the same random number generator instance with seed 69997.

The dotimes loop will then print 10 different pseudo-random numbers. If the rand was a new Random with seed 69997 every time, all 10 numbers would be exactly the same.

You can think of a function inside a closure as a static function using a static variable (in Java), but it's more than that, since the function will be able to access parameters on the global namespace and also in any other local namespace in which the let is declared. For example, another let, or even another defn!

(let [rand (java.util.Random. 69997)]

(defn rand-double []

(.nextDouble rand)))

(dotimes [i 10]

(println (rand-double)))

Above, note the dot '.' after Random, which indicates we are calling the constructor (with a single parameter 69997, the pseudorandom generator seed to be used). Alternatively, one may use the java-like syntax: (new java.util.Random 69997) -- note the absence of a dot now.

Manipulating images

ImageJ Image internals: ImagePlus, ImageProcessor, ImageStack

ImageJ has three basic objects:

- The ImagePlus, which wraps the ImageProcessor and contains properties and pointers to the ROI (region of interest) and the ImageWindow that may be displaying the image.

- The ImageProcessor, which is an abstract class enabling the high-level manipulation of and access to pixels. Its subclasses each wraps a different kind of data type:

- ByteProcessor - byte[]

- ShortProcessor - short[]

- FloatProcessor - float[]

- ColorProcessor - int[] (byte-packed ARGB, but Alpha channel is ignored)

- The ImageStack which contains unfortunately not an array of ImageProcessor, but an Object[] containing an homogeneous list of equal length byte[], or float[], etc.

For extensive documentation, see the Anatomy of an ImageJ image ImageJ programming basics tutorial.

Conventions in naming image variables

By convention, variables are named:

- imp to mean ImagePlus

- ip to mean ImageProcessor

- stack to mean ImageStack

Creating a new image

From scratch:

(import '(ij ImagePlus)

'(ij.process ByteProcessor))

(let [imp (ImagePlus. "A new image" (ByteProcessor. 400 400))]

(.show imp))

From a file:

(let [imp (IJ/openImage "/path/to/an/image.tif")] (.show imp))

Creating an image of the same type of an existing one

; The original

(def imp-1 (ImagePlus. "The source image" (FloatProcessor. 512 512)))

; The new empty image, of the same type as the old but larger

(def imp-2 (ImagePlus. "The larger image of the same type"

(.. imp-1 getProcessor (createProcessor 768 768))))

Above, notice the parenthesis (createProcessor 768 768), which specify for which method those numbers are arguments for.

Resizing an image

The idea is to grab the ImageProcessor, duplicate it and resize it. The resizing returns a new ImageProcessor of the same type:

(def imp-1 (IJ/openImage "/path/to/image1.tif")) (def imp-2 (ImagePlus. "A new larger one" (.. imp-1 getProcessor (createProcessor 1024 1024)))) ; Copy one into the other at top-left (hence 0,0 insert point): (doto (.getProcessor imp-2) (.insert (.getProcessor imp-1) 0 0))

An alternative way would be to simply duplicate the processor of imp-1, and then enlarge it:

(def imp-3 (ImagePlus. "A copy with extra empty space"

(.. imp-1 getProcessor duplicate (resize 768 768)))

Resizing an ImageStack

This one is harder, because an ImageStack is just a wrapper for Object[] list of pixel arrays. ImageJ though provides a mid-level resizing method, via the CanvasResizer class:

(import '(ij.plugin CanvasResizer)

'(ij IJ ImagePlus))

; Grab the image in the currently active ImageWindow:

(def imp-1 (IJ/getImage))

; function to resize images:

(defn resize-image

"Takes an ImagePlus as argument and returns a new ImagePlus

but resized to width,height, and with the contents copied

starting from xoff,yoff"

[imp w h xoff yoff]

(let [resizer (CanvasResizer.)

stack (.getStack imp)

imp-2 (ImagePlus. (.getTitle imp)

(if stack

(.expandStack resizer stack w h xoff yoff)

(.expandProcessor resizer w h xoff yoff)))]

imp-2))

(def imp-2 (resize-image imp-1 1024 1024 0 0))

(.show imp-2)

Note that the above function resize-image will work for both stacks and non-stack images.

Of course nothing stops you from looping through the stack length, calling a new ImageProcessor for each slice, resizing it, composing a new ImageStack and with it a new ImagePlus.

; Grab the image in the currently active ImageWindow:

(def imp-1 (IJ/getImage))

(defn resize-stack

"Resize an ImageStack to new widht,height

and copy its contents starting at xoff,yoff coordinate."

[stack w h xoff yoff]

(let [new-stack (ImageStack. w h nil)]

(doseq [i (range 0 (.getSize stack))]

(let [ip (.getProcessor stack (+ i 1))

#^ImageProcessor ip2 (.createProcessor ip w h)]

(.insert ip2 ip xoff yoff)

(.addSlice new-stack (str i) ip2)))

new-stack))

Above, note that stacks are 1-based,not 0-based!

Also, we must declare the type of the ip2 because clojure cannot decide between the ImageProcessor.addSlice(String,ImageProcessor) and ImageProcessor.addSlice(String,Object). You must make that choice for clojure.

Notice that each time you call getProcessor on an ImageStack, it returns a new ImageProcessor instance in a very costly way, by calling a series of instanceof on the pixels arrays to figure out which kind of ImageProcessor subclass it should create.

Resizing an image or ImageStack using ROIs

ROIs (aka Region of Interest or selection) have bounds, defined by the minimal enclosing rectangle.

The core idea is to set a ROI to an ImageProcessor and call crop to obtain a new, subcopy of it.

(def imp (IJ/getImage))

(def imp-cropped (ImagePlus. "Cropped"

(let [ip (.getProcessor imp)]

(.setRoi ip (Roi. 10 10 200 200))

(.crop ip))))

(.show imp-cropped)

To handle any ImagePlus (with single slice or containing an ImageStack, i.e. many slices), see this function:

(which assumes the ROI is contained fully within the image; otherwise for stacks it will throw an Exception stating that, rightly, dimensions do not match.)

(import '(ij.gui Roi)

'(ij ImagePlus)

'(ij.process ImageProcessor))

(def imp (IJ/getImage))

(defn crop-image

"Crop an image by the bounds of a ROI,

returning a new ImagePlus with the result."

[imp roi]

(let [crop-processor (fn [ip roi]

(.setRoi ip roi)

(.crop ip))

stack (.getStack imp)]

; Return a new ImagePlus with a new cropped ImageProcessor

; or a new cropped ImageStack:

(ImagePlus. (.getTitle imp)

(if stack

(let [box (.getBounds roi)

new-stack (ImageStack. (.width box) (.height box) nil)]

(doseq [i (range (.getSize stack))]

(.addSlice new-stack (.getSliceLabel stack (+ i 1))

#^ImageProcessor (crop-processor

(.getProcessor stack (+ i 1))

roi)))

new-stack)

; Else single slice image:

(crop-processor (.getProcessor imp) roi)))))

(def imp-cropped (crop-image imp (Roi. 100 100 300 300))

(.show imp-cropped)

The above works with both single images and stacks.

Manipulate images using ImgLib

With Imglib, pixels are stored in native arrays of primitives such as int, float, double, etc. (or other more interesting forms, such as Shape. Such pixels are accessed with intermediate proxy objects that the JIT is able to completely remove out of the way.

From Clojure, there are many ways in which to access the pixels. Here we list some examples of the pixels accessed as a Collection of accessor Type objects.

Multiply each pixel by 0.5

Multiply in place each value by 0.5. The ImgLib/wrap is a thin wrapper that accesses directly the pixel array. Hence the original image will be changed.

; ASSUMES the current image is 32-bit

(ns test.imglib

(:import [mpicbg.imglib.image Image]

[script.imglib ImgLib]

[mpicbg.imglib.type.numeric.real FloatType]

[ij IJ]))

(set! *warn-on-reflection* true)

(let [^Image img (ImgLib/wrap (IJ/getImage))

a (float 0.5)]

(doseq [^FloatType t img]

(.mul t a)))

In a more functional style, below we create an image with the same dimensions as the wrapped image, and set its pixel values to those of the original image times 0.5:

(ns test.imglib

(:import [mpicbg.imglib.image Image]

[mpicbg.imglib.cursor Cursor]

[script.imglib ImgLib]

[mpicbg.imglib.type.numeric NumericType]

[ij IJ]))

(set! *warn-on-reflection* true)

(let [^Image img (ImgLib/wrap (IJ/getImage))

a (float 0.5)

^Image copy (.createNewImage img "copy")]

(with-open [^Cursor c1 (.createCursor img)

^Cursor c2 (.createCursor copy)]

(loop []

(if (.hasNext c1)

(do

(.fwd c1)

(.fwd c2)

(let [^NumericType t1 (.getType c1)

^NumericType t2 (.getType c2)]

(.set t2 t1)

(.mul t2 a))

(recur)))))

(.. copy getDisplay setMinMax)

(.show (ImgLib/wrap copy)))

The above, though, is unbearably verbose. A high-level access to the images enables mathematical operations without trading off any performance:

(ns test.imglib

(:import [mpicbg.imglib.image Image]

[mpicbg.imglib.cursor Cursor]

[script.imglib ImgLib]

[script.imglib.math Compute Multiply]

[ij IJ]))

(set! *warn-on-reflection* true)

(let [^Image img (ImgLib/wrap (IJ/getImage))

^Image copy (Compute/inFloats (Multiply. img 0.5))]

(.. copy getDisplay setMinMax)

(.show (ImgLib/wrap copy)))

What's more, the Compute/inFloats method runs in parallel, with as many processors as your machine has cores. If you'd rather not execute the operation in parallel, add the desired number of threads as an argument to inFloats.

All mathematical operations listed in java.lang.Math have a corresponding constructor for execution in Compute/inFloats. See the documentation for the script.imglib.math package.

Normalize an image

Assumes that (IJ/getImage) returns a 32-bit, float image. If that is not the case, convert the image to a float image first.

The example below creates a new result image. The original image is untouched. This is accomplished with minimal friction but best performance (like hand-coded with cursors or better) by using the high-level scripting library of imglib, and the Compute/inFloats method.

(ns test.imglib

(:import [mpicbg.imglib.image Image]

[script.imglib ImgLib]

[script.imglib.math Compute Subtract Divide]

[ij IJ]))

(let [^Image img (ImgLib/wrap (IJ/getImage))

size (.size img)

mean (reduce

#(+ %1 (/ (.getRealFloat %2) size))

(float 0)

img)

variance (/ (reduce

#(+ %1 (Math/pow (- (.getRealFloat %2) mean) (float 2)))

(float 0)

img)

size)

std-dev (Math/sqrt variance)

^Image normalized (Compute/inFloats (Divide. (Subtract. img

mean) std-dev))]

(.. normalized getDisplay setMinMax)

(.show (ImgLib/wrap normalized)))

There is a better way to compute the mean and variance of a collection of numbers, that involves traversing the collection only once. Clojure naturally helps with its very concise destructuring and its automatic promotion of numeric types to avoid overflow.

(ns test.imglib

(:import [mpicbg.imglib.image Image]

[mpicbg.imglib.type.numeric RealType]

[script.imglib ImgLib]

[script.imglib.math Compute Subtract Divide]

[ij IJ]))

(set! *warn-on-reflection* true)

(let [^Image img (ImgLib/wrap (IJ/getImage))

size (.size img)

[xs x2s] (reduce (fn [accum ^RealType t]

(let [xi (.getRealFloat t)]

[(+ (accum 0) xi)

(+ (accum 1) (* xi xi))]))

[0 0]

img)

mean (/ xs size)

variance (- (/ x2s size) (* mean mean))

std-dev (Math/sqrt variance)

^Image normalized (Compute/inFloats (Divide. (Subtract. img mean) std-dev))]

(.. normalized getDisplay setMinMax)

(.show (ImgLib/wrap normalized)))

(Code adapted from a Common Lisp version by Patrick Stein.)

Looping an array of pixels

For example, to find the min and max values:

; Obtain the pixels array from the current image

(let [imp (ij.WindowManager/getCurrentImage)

pixels (.. imp getProcessor getPixels)

min (apply min pixels)

max (apply max pixels)]

(println (str "min: " min ", max: " max)))

The above code does not explicitly loop the pixels: it simply applies a function to an array.

To loop pixels one by one, use any of the following:

(let [imp (ij.WindowManager/getCurrentImage)

pixels (.. imp getProcessor getPixels)]

; First loop with "dotimes"

(dotimes [i (count pixels)]

(println (aget pixels i)))

; Second loop: with "loop -- recur"

(loop [i 0

len (count pixels)]

(if (< i len)

(do

(println (str i ": " (aget pixels i)))

(recur (inc i)

len)))))

Above, notice that the loop -- recur construct is essentially a let declaration, with a second call (recur) to reset the variables to something else. In this case, the next index in the array. Note how the len is simply given the same value over and over, just to avoid calling (count pixels) at each iteration.

Of course, there are lispier ways to loop an array of pixels. For example, to obtain the average of all pixels, we can use function reduce, which takes the first two elements of a list, applies a function to them, and then applies the function to the result and the next element, etc:

(let [fp (.getProcessor (ij.IJ/getImage))

pix (.getPixels fp)]

(if (instance? ij.process.FloatProcessor fp)

(println "Average pixel intensity" (/ (reduce + pix) (count pix)))

(println "Not a 32-bit image")))

Above, notice that one could have used also apply to apply + to all element of an array, with the same result:

(println "Average pixel intensity" (/ (apply + pix) (count pix)))

To sum all pixels in an 8-bit image, one needs first to bit-and all bytes to 255, so they become integers and can be summed. But of course we should not bit-and the sum! To solve this, reduce accepts a first value (in this case, zero):

(let [bp (.getProcessor (ij.IJ/getImage))

pix (.getPixels bp)]

(if (instance? ij.process.ByteProcessor bp)

(println "Average intensity: " (float (/ (reduce (fn [x1 x2] (+ x1 (bit-and x2 255))) 0 pix) (count pix))))

(println "Not an 8-bit image")))

It could even be done using a local variable, but it's ugly and undesirable (why create it when it's not really needed)? Notice we need to create the local variable "sum" because variables declared by let are immutable.

(let [bp (.getProcessor (ij.IJ/getImage))

pix (.getPixels bp)]

(if (instance? ij.process.ByteProcessor bp)

(with-local-vars (sum 0)

(doseq [pixel pix]

(var-set sum (+ (var-get sum) (bit-and pixel 255))))

(println (float (/ (var-get sum) (count pix)))))

(println "Not an 8-bit image")))

Any ImageJ menu command may be run on the active image:

(ij.IJ/doCommand "Add Noise")

Be aware that the above starts a new Thread and forks. For reliable control, try the run method, which will wait until the plugin finishes execution.

(ij.IJ/run "Add Noise")

For even more reliable control, run the command directly on a specified image, instead of a possibly changing current image:

(let [imp (ij.IJ/getImage)] (ij.IJ/run imp "Subtract..." "value=25"))

To find out which arguments can any command accept, open the Plugins - Macros - Macro Recorder and run the command manually.

Creating and using Clojure scripts as ImageJ plugins

Simply create a text file with the script inside, and place it in the plugins menu or any subfolder. Then call Plugins - Scripting - Refresh Clojure Scripts to make it appear on the menus.

If the macros/StartupMacros.txt includes a call to the Refresh Clojure Scripts inside the AutoRun macro, then all your Clojure scripts will appear automatically on startup.

To modify an script which exists already as a menu item, simply edit its file and run it by selecting it from the menus. No compiling necessary, and no need to call Refresh Clojure Scripts either (ther latter only for new scripts or at start up.)

Very important: all scripts and commands from the interpreter will run within the same thread, and within the same clojure context.

Using java beans for quick and convenient access to an object's fields

Essentially it's all about using get methods in a trivial way. For example:

(let [imp (ij.WindowManager/getCurrentImage)

b (bean imp)]

(println (:title b)

(:width b)

(:height b)))

Eventually Clojure may add support for set methods as well.

Examples

Fixing overexposed images: setting a pixel value to a desirable one for all overexposed pixels

The problem: Leginon or the Gatan TEM camera acquired an overexposed image, and set all pixels beyond range to zero.

The solution: iterate all pixels; if the pixel is zero then set it to a desirable value, such as the maximum value of the main curve in the histogram (push 'auto' on the Brightness and Contrast dialog to see it.)

In the example below, the fix function is called with the current image and the value 32500 as a floating point number. Notice also the type definition (which is optional) of the float pixel array, to enhance execution speed:

; Assumes a FloatProcessor image

(defn fix [imp max]

(let [#^floats pix (.getPixels (.getProcessor imp))]

(loop [i (int 0)]

(if (< i (alength pix))

(do

(if (= 0 (aget pix i)) (aset pix i (float max)))

(recur (inc i)))))))

(let [imp (ij.IJ/getImage)]

(fix imp (float 32500))

(.updateAndDraw imp))

Creating a script for ImageJ

Simply write the clojure script in a text file, and follow these conventions:

1. Add an underscore "_" to its file name, and the extension ".clj": fix_leginon_images.clj 2. Save it under fiji/plugins/ folder, or a subfolder.

When done, just run the PlugIns › Scripting › Refresh Clojure Scripts plugin.

Once saved and in the menus, you need not call refresh scripts ever again for that script. Just edit and save it's text file, and run it again from the menus. Next time Fiji opens, the script will automatically appear in the menus.

See Scripting Help for more details, including how to use the built-in dynamic interpreter.

Example Clojure plugins included in Fiji

Open the plugins/Examples/ folder in Fiji installation directory. You'll find three Clojure examples:

- Multithreaded_Image_Processing.clj: illustrate, with macros (via defmacro), how to automatically multithread the processing of an image using arbitrary subdivision of the image, such as one line per thread, for as many threads as cores the CPU has.

- blend_two_images.clj: illustrates how to open two images from an URL, and blend the gray image into each channel of the color image.

- celsius_to_fahrenheit.clj: illustrates the usage of a Swing GUI, and how to instantiate anonymous classes from an interface (via proxy Clojure function). This example is taken from the Clojure website.

- random_noise_example.clj: illustrates how to declare a function inside a closure (for private access to, in this case, a unique instance of a random number generator), and then fill all pixels of a ByteProcessor image with a random byte value.

- Command_Launcher_Clojure.clj: illustrates how to create a GUI with a KeyListener, so that the typed text changes color from red to black when it matches the name of an ImageJ command. This example is also under the Scripting comparisons, along equivalent versions written in Java, Jython, Javascript and JRuby.

- Dynamic ROI Profiler: illustrates how to add a MouseMotionListener and a WindowListener to an ImageWindow of an open image. Reads out the ROI (Region Of Interest), and if it's a line, polyline or rectangle, plots the profile of pixel intensity along the line. As the mouse moves or edits the ROI on the image, the profile is updated.

Appendix

Defining the output stream

The default output stream is at variable *out*, which you may redefine to any kind of PrintWriter:

(let [all-out (new java.io.StringWriter)]

(binding [*out* all-out]

; any typed input here

; All calls to pr, prn, println will print into all-out

(println "this and that")

)

; Now show any printed out text in ImageJ's log window:

(ij.IJ/log (str all-out)))

Destructuring

Destructuring is a shortcut to capture the contents of a variable into many variables.

An example: when looping a map, we get the entry, not the key and value of each entry:

(doseq [e {:a 1 :b 2 :c 3}]

(println e))

Prints:

[:a 1] [:b 2] [:c 3] nil

Each "entry" is represented by a vector with two values.

Now to loop more conveniently, we can assign the key and value to variables, by what is called destructuring (note the [k v] where the e was before)

(doseq [[k v] {:a 1 :b 2 :c 3}]

(println k v))

Prints:

:a 1 :b 2 :c 3 nil

Even better, we can preserve the whole entry as well, by using the keyword ":as":

(doseq [[k v :as e] {:a 1 :b 2 :c 3}]

(println k v e))

Prints:

:a 1 [:a 1] :b 2 [:b 2] :c 3 [:c 3] nil

Namespaces

- To list all existing namespaces:

>>> (all-ns) (#<Namespace: xml> #<Namespace: zip> #<Namespace: clojure> #<Namespace: set> #<Namespace: user>)

- To list all functions and variables of a specific namespace, first get the namespace object by name:

(ns-map (find-ns 'xml))

Note above the quoted string "xml" to avoid evaluating it to a (non-existing) value.

- To list all functions and variables of all namespaces:

(map ns-map (all-ns))

A nicer way to print all public functions and variables from all namespaces, sorted alphabetically:

(doseq [name (all-ns)]

(doseq [[k v] (sort (ns-publics name))]

(println k v)))

Note above we use destructuring: the [k v] take the values of the key and the value of each entry in the ns-publics table. Actually, since we first sort the table, the k and v take the first and second values of each array pair in the sorted list of array pairs returned on applying sort to the ns-publics-generated table.

Forget/Remove all variables from a namespace

To forget all variables from the user namespace, do:

(map #(ns-unmap 'user %)

(keys (ns-interns 'user)))

The above maps the function ns-unmap to each variable name declared in the user namespace (using # to create a lambda function), which is the same as the prompt namespace. To get the names of the variables, we use ns-interns to retrieve the map of variable names versus the variable contents, and extract the keys from it into a list.

Thanks to AWizzArd from #clojure at irc.freenode.net for the tip.

JVM arguments

- To get the arguments passed to the JVM, see contents of variable *command-line-args*

(println *command-line-args*)

Reflection

- To list all methods of an object:

(defn print-java-methods [obj]

(doseq [method (seq (.getMethods (if (= (class obj) java.lang.Class)

(identity obj)

(class obj))))]

(println method)))

; Inspect an object named imp, perhaps an image

(print-java-methods imp)

public synchronized boolean ij.ImagePlus.lock()

public void ij.ImagePlus.setProperty(java.lang.String,java.lang.Object)

public java.lang.Object ij.ImagePlus.getProperty(java.lang.String)

...

- To list constructors, just use .getConstructors instead of .getMethods.

(Thanks to Craig McDaniel for posting the above function to Clojure's mailing list.)

Lambda functions

Declaration

- To declare functions on the fly, lambda style, with regex for arguments:

For example, declare a function that takes 2 arguments, and returns the value of the first argument divided by 10, and multiplied by the second argument:

(let [doer #(* (/ %1 10) %2)] (doer 3 2))

Of course there's no need to name the function, the above is just for illustration.

Mapping a function to all elements in a list

- To declare a nameless function, and apply it to each element of a list:

In this case, increment by one each value of a list from 0 to 9:

(let [numbers (range 10)

add-one (fn [x] (+ x 1))]

(map add-one numbers))

There is no need to declare the names, the above is just for illustration. Above, we could have defined the function as #(+ %1 1):

(map #(+ %1 1) (range 10))

... or of course use the internal function inc which does exactly that:

(map inc (range 4))

Beware that the map function above applies the given function to each element of a list, and returns a new list with the results.

Built-in documentation

Use the function doc to query any other function or variable. For example, the list generator function range:

(doc range) ------------------------- clojure/range ([end] [start end] [start end step]) Returns a lazy seq of nums from start (inclusive) to end (exclusive), by step, where start defaults to 0 and step to 1.

Above, notice the function has three groups of possible arguments, denoted in brackets.

When not knowing what to search for, you may try find-doc instead, which takes a string or regular expression as argument:

user=> (find-doc "ns-") ------------------------- clojure.core/ns-aliases ([ns]) Returns a map of the aliases for the namespace. ------------------------- clojure.core/ns-imports ([ns]) Returns a map of the import mappings for the namespace. ... etc.

Defining documentation for your own functions

So where does the documentation come from? Every definition of a function or macro or multimethod may take a description string before the arguments:

(defn area "Computes the area of a rectangle." [r] (* (.width r) (.height r)))

... which the doc function prints, formatted:

user=> (doc area) ------------------------- user/area ([r]) Computes the area of a rectangle. nil

Defining documentation for a variable

(def

#^{:doc "The maximum number of connections"}

max-con 10)

... which the doc function prints as:

user=> (doc max-con) ------------------------- user/max-con nil The maximum number of connections nil

Function documentation is internally set like the above: defn is a macro that defines a function and puts the second argument as the doc string of the variable that points to the function body (among many other things).

Adding a test function to a variable

We first declare the variable, and then define it with a metadata map that includes a test function:

(declare a)

(def

#^{:test #(if (< a 10) (throw (Exception. "Value under 10!")))}

a 6)

... which we then test, by invoking the function test not on the value of the variable a (which could have its own metadata map), but on the variable a itself, referred to with the #'a:

(test #'a)

The test results, in this case, in an exception being thrown:

java.lang.Exception: Value under 10!

Otherwise, it would just return the :ok keyword.

A fibonacci sequence: lazy and infinite sequences

A beautiful example of using lazy sequences and applying functions to one or more sequences at a time.

Below, the sequence fibs is defined in such a way that it contains all possible fibonacci numbers. Since such sequence is infinite, we declared it as lazy sequence, that creates new elements only when they are asked for.

The lazy-cat clojure function creates such lazy sequence by concatenation of two sequences: the first sequence is 0, 1 (which takes the role of feeder or initialization sequence), and the second sequence is the result of a map operation over two subsets of the fibs sequence itself: the full and the full minus the first element (hence the rest operation to obtain the list of all elements without the first).

A map operation applies a function to each element of a sequence, or, when two or more sequences are provided, to the corresponding elements: those at index 0 in all sequences, those at index 1 in all sequences, etc.

To generate the fibonacci sequence of numbers, a sum + operation is mapped to the numbers contained in the self sequence fibs and to the corresponding elements of the self sequence fibs minus the first element, i.e. shifted by one.

In short, the lazy sequence fibs is an abstract way of representing a potentially infinite sequence, with an implementation containing a full abstract definition of all fibonacci numbers.

Then we just take the first 10 elements of such lazy sequence, which are created on the fly.

(def fibs (lazy-cat [0 1]

(map + fibs (rest fibs))))

(take 10 fibs)

Which outputs:

(0 1 1 2 3 5 8 13 21 34)

Printing lazy sequences to the REPL

The REPL, when given a lazy sequence, will traverse it in its entirety to print it.

Printing a potentially infinite lazy sequence to the REPL is something you don't want to do: besides triggering computation of each element, it would fill all memory and throw an OutOfMemoryException. And you'd get bored seeing elements pass by.

A good option is to print only part of it:

- take: the first N elements.

- drop: all elements beyond N.

- nth: the nth element only.

For infinite lazy sequences, drop wouldn't save your REPL, and take could be perhaps too many still.

To avoid accidental printing of complete lazy-sequences, you may set *print-length* to a reasonable number:

(set! *print-length* 5)

So now one can safely print the entire fibonnaci sequence, which will print only the first 5 elements, followeed by dots:

user=> (set! *print-length* 5) 5 user=> fibs (0 1 1 2 3 ...)

The *print-length* applies to all sequences to be printed in the REPL, but is specially useful for very large lazy sequences.

Creating shallow and deep sequences from java arrays

Many clojure functions take sequences, not native java arrays, as arguments. A java native array can be wrapped by a shallow sequence like the following:

>>> (def pixels (into-array (range 10))) #'user/pixels >>> pixels [Ljava.lang.Integer;@f30d8e >>> (def seq-pix (seq pixels)) #'user/seq-pix >>> seq-pix (0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9)

Now if we modify the native array, the sequence will reflect that change too when read:

>>> (aset pixels 3 99) 99 >>> seq-pix (0 1 2 99 4 5 6 7 8 9)

The array was not duplicated. The only new object created was the shallow sequence:

>>> (class seq-pix) clojure.lang.ArraySeq

To create a true deep duplicate of the array, one can do:

>>> (def pixels2 (vec pixels)) #'user/pixels2 >>> (class pixels2) clojure.lang.LazilyPersistentVector >>> pixels2 [0 1 2 99 4 5 6 7 8 9] >>> (def seq-pix2 (seq pixels2)) #'user/seq-pix2 >>> (class seq-pix2) clojure.lang.APersistentVector$Seq

Or, in short:

(def seq-pix2 (seq (vec pixels))) #'user/seq-pix2

So now any changes to the original pixels array will not affect the new sequence:

>>> (aset pixels 3 101) 101 >>> seq-pix2 (0 1 2 99 4 5 6 7 8 9)

Thanks to Chouser and wwmorgan for examples on #clojure at irc.freenode.net

Generating java classes in .class files from clojure code

Using ahead of time (AOT) compilation with gen-class, any clojure code can be compiled to a java class. Such class can then be used from java code, or from any scripting language like jython, jruby, javascript, and any other.

One way to do so is to place a gen-class declaration in a namespace block.

Be aware: the namespace must match the folder structure where the .clj file is and the file name of the .clj file. For example, to generate a class named fj.tests.process.FloatProcessorPlus, you need a clojure file under fj/tests/process/FloatProcessorPlus.clj .

To compile the clojure code to .class files, you need:

- A classes/ folder in the current directory where clojure.lang.Repl is run. This folder will receive the generated .class files.

- Add to your classpath the top-level folder, in the example the 'fj' folder, and also the folder containing the .clj file itself.

- Add to your classpath the classes/ folder as well.

- In a clojure.lang.Repl, use the compile function.

For example:

$ mkdir classes $ java -cp .:../../ij.jar:../../jars/clojure.jar:./classes/:./fj/tests/process/ clojure.lang.Repl

user=> (compile 'fj.tests.process.FloatProcessorPlus) fj.tests.process.FloatProcessorPlus user=>

The following clojure example contains a namespace declaration that includes some imports and also the gen-class. In the gen-class block, we define which class our code extends (in this case, ij.process.FloatProcessor), and which methods are to be created (with specific argument signatures and return object signature).

Later, the compiler will assign a clojure function to each declared method, using the prefix string plus the method name to match a function.

For example, with prefix "fp-" and method "fillValue", the compiler will look for the clojure function "fp-fillValue".

Finally, a main method is not directly declared, but exists if a function named prefix + main ("fp-main" in the example) exists. We can use the main method to run the new class as an application.

The example clojure code:

; Albert Cardona 20081203

; Save this file as fj/tests/process/FloatProcessorPlus.clj

; and compile it from a Repl or clojure script like:

;

; (compile 'fj.tests.process.FloatProcessorPlus)

;

; Be sure to set the classpath to point to the folder containing the above file, for example:

; $ cd fiji/plugins/

; $ mkdir -p tests/fj/tests/process

; $ cd tests/fj/tests/process/

; $ vim FloatProcessorPlus.clj

; ...

; $ cd ../../../

; $ mkdir classes

; $ java -cp ../../ij.jar:../../jars/clojure.jar:./classes/:.:./fj/tests/process/ clojure.lang.Repl

; user=> (compile 'fj.tests.process.FloatProcessorPlus)

; fj.tests.process.FloatProcessorPlus

; user=>

;

; The compilation will place the proper .class files under the proper directory

; structure in the ./classes/ folder.

;

; Then run like any other java class with a static public void main method:

; $ java -cp .:../../ij.jar:../../jars/clojure.jar:./classes fj.tests.process.FloatProcessorPlus

;

(ns fj.tests.process.FloatProcessorPlus

(:import (ij ImagePlus)

(ij.process FloatProcessor)

(java.util Random))

(:gen-class

; Could also use :implements

:extends ij.process.FloatProcessor

; Specify methods to expose as public,

; with specific parameter types and return type:

:methods [[fillMin [] void]

[fillMax [] void]

[fillValue [float] void]

[randomize [] void]]

; Define a function prefix for the exposed methods: for example,

; the fillMin public method is implemented by function fp-fillMin.

:prefix "fp-"))

(defn fp-fillValue [this value]

"Set each pixel in the image to the given value."

(.setPixels this

(into-array Float/TYPE (replicate

(* (.getWidth this) (.getHeight this))

(float value)))))

(defn fp-fillMin [this]

(.fillValue this Float/MIN_VALUE))

(defn fp-fillMax [this]

(.fillValue this Float/MAX_VALUE))

; Declaring a function to be used as a java method, within a closure:

(let [generator (Random. (System/currentTimeMillis))]

(defn fp-randomize [this]

(.setPixels this (into-array Float/TYPE

(map

(fn [x] (.nextFloat generator))

(range (* (.getWidth this) (.getHeight this))))))))

; This function is seen as the static public void main function of a java class:

; (add a parameter, like [args], if you would like to access the command-line args)

(defn fp-main []

"Test the generated class"

(let [imp (ImagePlus. "Test" (fj.tests.process.FloatProcessorPlus. 100 100))

ip (.getProcessor imp)] ; Testing access on "ImageProcessor" type

(.show imp)

; Test some methods of our extended FloatProcessor class:

(.randomize ip)

(.findMinAndMax ip)

(.updateAndDraw imp)))

References, concurrency, transactions and synchronization

Clojure supports thread concurrency without explicit locks. Compared to java code, this is a gigantic step forward: locks, and particularly multiple locks, are very hard to get right and very, very hard to debug properly (but see debugging multithreaded java programs).

The most basic building blocks are references, which are created with the ref function, and modified within transaction blocks (defined by dosync) using commute or alter functions (and others).

To read out the value of a reference, call deref or just @ on it:

; Create a new reference named 'id' initializated to value zero: (def id (ref 0)) -> 0 ; Read out the value of the reference: @id -> 0 ; Increase the id by one, using built-in function "inc": (dosync (alter id inc)) -> 1 ; Set the value to 20 (ignoring the current value, given in cv: (dosync (alter id (fn [cv] 20))) -> 20

References are not type specific: any object may be assigned to the same reference. Whether that makes any sense is up to you.

The commute and alter functions replace the value of the reference with that of the return value of a function given as argument. The function given as argument to commute and alter is given, in turn, the value of the reference (i.e. the dereferenced reference) and any other further arguments. The difference between commute and alter is that commute returns the dereferenced reference after the transaction is done, which may be different already (because of concurrent modifications) than the value that was set to the reference within the transaction; whereas alter returns the value that it had while the transaction was being done (i.e. the value returned by the function, the same that gets set as the value of the reference).

In the following example, a unique id counter is incremented continuously by 1, and all ids are collected, unordered, into a vector. Both the next available id and the vector of all accessed ids are stored in references.

Keep in mind the vector of ids assigned to the reference named 'ls' is always immutable: what we assign to the reference 'ls' below is a new vector, resulting from adding a new id to the old vector of ids. This immutability enables other threads to read the vector without locks. For performance, keep in mind that vectors, like many other clojure data structures, have structural sharing, so the new vector is not a duplication--even if it behaves like one.

The assignment is done in a transaction, so no matter how many concurrent threads try to do so, the resulting vector will have all the ids.

; Albert Cardona 2008-12-18

; Example clojure program using references and concurrent threads

; that alter the value of the references.

;

; 10 threads running concurrently

; each thread runs 100000 iterations

; in each iteration the thread increments a counter 'id'

; and adds it to a list 'ls' of ids.

; At the end, we print the current value of 'id'

; and the length of the list 'ls' of ids.

;

; No locks!

(ns fj.test.concurrent

(:import (java.util.concurrent Executors TimeUnit)))

(let [ls (ref []) ; A reference to a vector storing a list if ids.

id (ref 0) ; The next unique id available.

n_threads 10

n_iterations 100000

exec (Executors/newFixedThreadPool n_threads)]

(println "Running" n_threads "threads x" n_iterations "iterations/thread...")

(dotimes [i n_threads]

(.submit exec (fn []

(dotimes [t n_iterations]

; Obtain the next unique id:

; (Note we use "alter" and not "commute", because alter

; returns the result of the applied function, whereas

; commute would return the dereferenced ref, which could

; have already changed. Thanks to AWizzards for spotting

; this.)

(let [next-id (dosync (alter id inc))]

; Create a new vector made of

; all previous ids and next-id,

; and set it as the current list of ids:

(dosync (commute ls conj next-id)))))

nil))

(.shutdown exec)

(.awaitTermination exec 10 TimeUnit/MINUTES)

(println "... done!")

; If there was any clash in setting the reference to the list of ids,

; the count would be less than 1000000:

(println "Number of listed ids:" (count @ls))

; If any id was used twice, the next available id would be less than 1000000:

(println "Next available id:" @id)

; Check that there aren't any repeated ids:

(println "Number of repeated ids:"

(- (count @ls)

(count (set @ls))))) ; Make a hash set (with unique entries) from the list of ids

Using try/catch/finally and throwing Exceptions

(try

(println "Going to throw ...")

(throw (Exception. "Testing error catching"))

(println "Should not print, an Exception is thrown before")

(catch Exception e

(println "Oops ... an error ocurred.")

(.printStackTrace e))

(finally

(println "Cleaning up!")))

Of course you can throw any kind of exception you want. For example, in checking function arguments:

(import '(java.awt Rectangle))

(defn area [#^Rectangle r]

(if (not (instance? Rectangle r))

(throw (IllegalArgumentException. "Can only compute the area of a Rectangle.")))

(* (.width r) (.height r)))

Above, despite the type declaration, one can pass any value to the area function and it will still work, but of course our class check will cut execution:

user=> (area 10) java.lang.IllegalArgumentException: Can only compute the area of a Rectangle. (NO_SOURCE_FILE:0) user=> (area (Rectangle. 0 0 10 10)) 100

Executing a command in a shell and capturing its output

First we define the macro exec:

(import '(java.io BufferedReader InputStreamReader))

(defmacro exec

"Execute a command on the shell, passing to the given function

the lazy sequence of lines read as output, and the rest of arguments."

[cmd pred & args]

`(with-open [br# (BufferedReader. (InputStreamReader. (.getInputStream (.exec (Runtime/getRuntime) ~cmd))))]

(~pred (line-seq br#) ~@args)))

Some explanations on the above macro syntax (see also clojure's macro syntax page):

- The backquote ` quotes the next expression, as defined by: `( <any code here> ). Which means the code block is not evaluated. But, unlike simple quote ', the backquote enables evaluation of expressions within the block when tagged with a ~ (a tilde).

- The ~ (tilde) evaluates the immediate expression. Can only be used in the context of a backquoted code block.

- The ~@ means evaluate and expand, which has the efect of placing the elements of a list as if they where declared in the code, without the list enclosure. So: `(~@(str "this" "that")) results in: "thisthat". In the example above, we expand the & args, which is a list containing all arguments given to the exec macro beyond the first and second (which are bound to cmd and pred, respectively). In this way, we lay down the proper function call of the pred, which is expected to be a function name (a predicate); the reason we use ~ on it is to evaluate pred so that it renders the pointer to the function itself. That pred function, by design, must accept a lazy sequence of text lines and any number of arguments afterwards.

- The # tagged at the end of a name expands to (gensym name), which results in creating a uniquely named symbol, to avoid name collisions.

- Any code present outside the backquote (none, in the case above) will be executed at macro read time, not at code execution time (aka run time)! So any precomputations are possible before laying down the code that will be executed at run time.

Then we give the macro a command to execute and a function to process its stdout output.

; List all files in the home directory:

(exec "ls /home/albert/"

#(doseq [line %1] (println line)))

A second example, printing the file size of each listed file in the home directory:

; Print the size of each file in the home directory:

(import '(java.io File))

(let [dir "/home/albert/"]

(exec (str "ls " dir)

#(doseq [line %1]

(println (.length (File. (str dir line)))))))

A third example, telling the music player XMMS2 to jump to a specific track in its playlist:

(let [track-number 125]

(exec (str "xmms2 jump " track-number)

(fn [lines] lines)))

The above is an extract from a clojure GUI for XMMS2, available at github xmms2-gui.

Creating a derivative of a function

The derivative of a function:

We can approximate the derivative by choosing an arbitrarily precise value of the increment dx.

So first we define a function that takes any function as argument and returns a new function that implements its derivative. For convenience, we define it within a closure that specifies the arbitrarily precise increment dx (but we could just pass it as argument):

(let [dx (double 0.0001)]

(defn derivative [f]

"Return a function that is the derivative of the given function f, using dx increments."

(fn [x]

(/ (- (f (+ (double x) dx))

(f x))

dx))))

Then, for any example function like the cube of x:

(defn cubic [x]

(let [a (double x)]

(* a a a)))

... we create its derivative function, which we place into a variable (note we use def and not defn):

(def cubic-prime (derivative cubic))

We can now call the cubic-prime function simply like any other function:

(cubic-prime 2) -> 12.000600010022566 (cubic-prime 3) -> 27.00090001006572 (cubic-prime 4) -> 48.00120000993502

The derivative of x^3 is 3 * x^2, which for an x of 4 equals 48. Our derivative is as precise as low is the value of the increment dx.

The above code translated from lisp code at funcall blog. Thanks Joe Marshall for sharing this perl.

Pretty printing a primitive array

Suppose we create a primitive array of length 10:

user=> (def pa (make-array Integer/TYPE 10))

If we print it, we get:

user=> (println pa) #<int[] [I@169bc15>

... which is not very useful. Instead, let's pretty print it.

First, import the function pprint (and many other functions) from clojure-contrib pprint namespace:

user=> (use 'clojure.contrib.pprint)

Then, use it:

user=> (pprint pa) [0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0]

A similar result can be obtained by wrapping primitive arrays with seq, which generates a Collection view on the primitive array:

user=> (println (seq pa)) [0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0]

That seq creates only a view (and not a copy), you can convince yourself: changing the array changes the view, too:

user=> (def sa (seq pa)) user=> sa [0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0] user=> (aset pa 3 7) user=> (pprint pa) [0, 0, 0, 7, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0] user=> sa [0, 0, 0, 7, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0]

Loading an image file into a byte array

(import [java.io File FileInputStream]

(defn ^bytes load-file

"Load a file into a byte array."

[filepath]

(let [^File f (File. filepath)

len (int (.length f))

^bytes b (byte-array len)]

(with-open [^FileInputStream fis (FileInputStream. f)]

(loop [offset (int 0)]

(if (< offset len)

(recur (unchecked-add offset (.read fis b offset (unchecked-subtract len offset)))))))

b))

... which then may be parsed as a java.awt.Image:

(def img (javax.imageioImageIO/read

(java.io.ByteArrayInputStream.

(load-file "/home/acardona/Desktop/t2/NileBend.jpg"))))

... which then may be shown as an ImagePlus:

(.show (ij.ImagePlus. "nile bend" img))